Language and genes often tell different stories. Archaeogenetics shows that while migrations shape populations, cultural and political shifts can transform language far beyond their genetic footprint. From Gaul to the British Isles, from the Urals to North Africa, history offers many examples where tongues moved faster than chromosomes.

1. France – Latin Speech, Celtic Genes

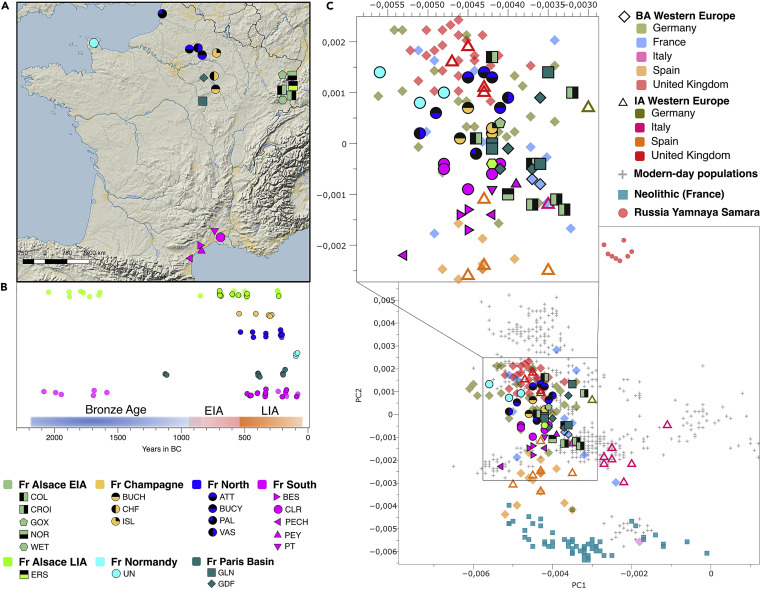

After the Roman conquest, Gaul adopted Latin, which evolved into French and other Romance languages. Yet genome-wide studies reveal deep continuity between Iron Age Gauls and modern French. In the Fisher et al., 2022 study (Cell Reports), the PCA shows Iron Age and modern French individuals clustering almost identically, proving that Romanization was cultural, not genetic.

Reference: Fernandes, D. M. et al. 2022 – The origin and legacy of the Gauls.

Takeaway: France speaks a Latin language, but its people are still the descendants of Iron Age Gauls.

2. Hungary – Uralic Speech, European DNA

The Magyar tribes who arrived from the southern Urals in the 10th century introduced a Uralic language to the Carpathian Basin. Ancient DNA from their elite burials shows steppe-Uralic ancestry, yet the wider Hungarian population remained largely Central-European in genetic structure. Modern Hungarians cluster closely with their Slavic and Germanic neighbors, not with Siberian Uralics.

Reference: Long shared haplotypes identify the southern Urals as a primary source for the 10th-century Hungarians, 2024.

Takeaway: The Magyars changed Hungary’s language through elite dominance, not mass migration.

3. Finland – Uralic Language, Mostly European Genome

Finns speak a Uralic language, but genetically they are Northern Europeans with only a modest Siberian “pull.” On PCA plots, Finns lie slightly northeast of other Scandinavians, reflecting small Nganasan-related ancestry introduced during the Bronze or Iron Age. The linguistic impact of early Uralic expansion far exceeded the demographic one.

References:Lamnidis et al., 2018 (Nature Communications).

Takeaway: A minor Siberian genetic input created a major linguistic boundary.

4. North Africa – Arabic Speech, Amazigh Genes

Arabic replaced Berber languages over the past 1,300 years, but DNA shows the region remains overwhelmingly indigenous. Studies (Fadhlaoui-Zid et al., 2024) reveal that “Arab” and “Berber” speakers share the same ancient North-African ancestry, with only limited Near-Eastern admixture dating to the Islamic expansion. PCAs show a continuous Maghrebi cline, not a clear Arab–Berber divide.

Takeaway: Arabization spread through religion, trade, and administration—not by massive settlement.

5. Britain – English Language, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Genes

After the Norman Conquest (1066 CE), the English language absorbed a flood of Norman French vocabulary, eventually becoming the hybrid Germanic–Romance tongue we speak today. However, the English gene pool remained nearly identical to that of earlier Anglo-Saxon and Iron Age groups. PCA results from Gretzinger et al., 2022 (Nature Communications)show modern English clustering tightly with early medieval Anglo-Saxons and earlier Celto-Roman Britons. The Norman elite left virtually no genetic trace, yet profoundly shaped the language and culture.

Takeaway: England became linguistically half-French, but genetically stayed British.

The Global Pattern

| Region |

Incoming Language |

Genetic Continuity |

Mechanism |

| France |

Latin (Roman) |

High (Iron Age Gaulish base) |

Cultural prestige, administration |

| Hungary |

Uralic (Magyar) |

Very high |

Elite dominance |

| Finland |

Uralic |

High with minor Siberian input |

Northern expansion, assimilation |

| North Africa |

Arabic |

Very high |

Religion, governance |

| Britain |

English (Norman influence) |

High |

Cultural diffusion, elite bilingualism |

Conclusion

From the Atlantic to the Urals and the Sahara, language is not destiny. DNA preserves deep continuity; languages follow history, conquest, and aspiration. Each PCA tells the same story: the people often stay, but their words can travel.