In the silence of a 5th-century cemetery in Angers, in the heart of what is now western France, a man was buried. More than a millennium later, he would be given the code name FRA009, and his DNA would tell an unexpected story—a story that stretches across the Mediterranean, from North Africa to the Loire Valley.

Sequenced as part of a large-scale study of French genetic history published in Nature Communications (2024), FRA009 stood out as an anomaly. While all other medieval individuals clustered genetically with modern or ancient western Europeans, FRA009 showed a strong affinity with present-day North Africans. His mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, as well as his Y-chromosome haplogroup E-FTG24236, all point to a recent North African origin, making him a rare and precious witness of long-distance mobility in post-Roman Europe.

The Context: A Roman Town in Transition

FRA009 was found in Angers (ancient Juliomagus), a significant town in Roman Gaul that retained strategic and religious importance well into the early medieval period. Around 414–548 CE, when FRA009 was buried, the Western Roman Empire was collapsing. Visigoths ruled in Aquitaine, Franks were rising in the north, and imperial authority was fragmenting—but Roman towns like Angers remained populated and relatively stable.

Archaeological records from Angers indicate continuity in urban life, a blend of Gallo-Roman traditions and emerging early Christian influence. FRA009’s burial is part of this hybrid cultural moment—yet his genome places him far from the local population.

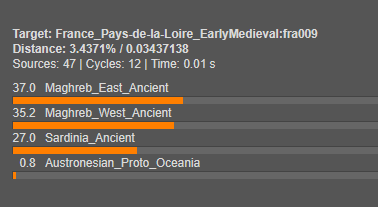

The Genetics: A North African Profile

The genome-wide data places FRA009 well outside the variation of early medieval and modern French populations. Instead, his closest genetic relatives are modern North Africans, likely from the Maghreb, such as Algeria or Tunisia. This signal is not a trace of distant ancestry—it suggests that FRA009 himself, or one of his parents, was born in North Africa.

This is confirmed by his Y-DNA haplogroup E-FTG24236, a lineage belonging to E-M78, a branch commonly found in North Africa, particularly among Berber populations. This lineage is extremely rare in continental Europe, especially in ancient contexts. Its presence in FRA009 implies a recent introduction of this paternal lineage into Gaul.

Contamination was ruled out (estimated at ~4%), and the sample passed all authenticity checks.

How Did FRA009 Get There? Possible Scenarios

The presence of a man with North African ancestry in 5th-century Angers raises fascinating questions. Here are the most plausible scenarios:

1. A Roman Soldier or Auxiliary (Late 4th–5th c. CE)

The Roman army regularly recruited soldiers from across the empire—including North African provinces like Mauretania and Numidia. North African units served along the Rhine frontier and in Gaul. FRA009 could have been a retired soldier or the descendant of one, settled in Angers after service.

Supporting evidence:

-

Historical records of Berber units in Gaul.

-

Roman practice of settling veterans with land.

-

Roman military continuity into the 5th century in western towns like Angers.

2. A Merchant or Diplomat from North Africa

Trade and diplomacy between North Africa and Gaul persisted even after the Vandals conquered Carthage in 439 CE. Angers, while not a major port, was linked to the Loire trade route. FRA009 may have been part of a merchant family, embassy, or religious mission.

Supporting evidence:

-

Trade in oil, grain, and pottery continued across the Mediterranean.

-

Religious emissaries (e.g., monks, bishops) traveled between Gaul and Africa.

-

Cultural exchange persisted in Christian networks.

3. A Refugee from the Vandal or Byzantine Conflicts

With the Vandal conquest of North Africa and the Byzantine reconquest in 533–534 CE, many urban elites, soldiers, and Christians fled the region. FRA009 could have been a first-generation migrant displaced by conflict—perhaps a Christian seeking asylum in Gaul.

Supporting evidence:

-

Historical mentions of African Christians seeking refuge in Gaul and Italy.

-

The time window (414–548 CE) overlaps both conflicts.

-

Cultural similarities between late antique North Africa and Gallo-Roman towns.

4. A Descendant of Roman-Era Africans Settled Earlier in Gaul

Another hypothesis is that FRA009 descended from a North African individual settled in Gaul during the Roman Empire, perhaps in the 2nd–3rd century CE. If this lineage remained somewhat isolated, his DNA could still reflect North African ancestry strongly.

Supporting evidence:

-

Afro-descendants existed in the Roman Empire (e.g., Severan family, African legionnaires).

-

North African migrants were present in Roman Britain and Gaul.

-

Less likely if no admixture is observed, which suggests more recent ancestry.

5. An Enslaved Individual or Freedman

Slavery persisted well into late antiquity. FRA009 may have been brought to Gaul as a slave or servant, later integrated into local society. His proper burial suggests he died as a free man, possibly with a family or community.

Supporting evidence:

-

Slaves from North Africa were traded across the empire.

-

Integration and manumission were common.

-

Burial in an urban cemetery implies social inclusion

A Human Story Behind the Genome

FRA009 may have spoken Latin or Berber, or perhaps both. He might have prayed in a Christian basilica, traded in local markets, or served in a garrison. He was part of the multicultural mosaic of late Roman Gaul, a man whose life bridged continents.

His bones remind us that migration is not a modern story—it's a deeply human one. In FRA009, we see the Mediterranean not as a barrier, but as a bridge, connecting Africa and Europe long before modern borders were drawn.

For those interested in further analysis or visualization, here are the G25 coordinates of the sample:

Copy to clipboard

France_Pays-de-la-Loire_EarlyMedieval:fra009,-0.007968,0.139128,-0.002640,-0.066215,0.035699,-0.037929,-0.026321,0.007846,0.061766,0.027335,-0.001949,-0.005545,0.006690,-0.020093,0.005972,-0.008088,0.012386,-0.013176,-0.029288,0.001751,-0.005241,-0.032521,0.026252,0.000120,0.005269

Reference: Alves et al. (2024), "Human genetic structure in Northwest France provides new insights into West European historical demography", Nature Communications, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51087-1.